narrative debt collectors

Every time you flag something as important, you sign a promise — here’s how not to default on it.

(Quick note: after receiving this lovely email, I’ve changed the status of an older article to be free now for new subscribers — it’s on writing, learning, AI, abundance, and self-challenge. It meant a lot to me to hear this, so thank you Elly!)

Now for our next article…

Narrative Debt Collectors

Every time you flag something as important, you sign a promise — here’s how not to default on it.

When players talk about wanting choices to 'matter,' it's often less about desiring galaxy-altering consequences and more about feeling their investment and emotional energy rewarded and acknowledged within the game. Providing opportunities for the player to feel 'seen’ by a game doesn't demand massive divergence or branching; it’s about acknowledging what is likely to feel salient for the audience.

Shaping Salience

By salient, I mean relevant for the moment in question. This relevance will always vary across individuals and groups according to personal tastes, experiences, and what earlier narrative encounters have taught us to value. However, focusing solely on player interpretation risks ignoring the responsibility and power we have as narrative creators to shape the salience of various points at specific moments.

This shaping of salience is demonstrated if you think about the way twists work. Powerful twists land effectively because of negative space – we fairly set up the information required to know the truth but then engage in distraction and misdirection to encourage the audience to look elsewhere. This setup leads to the crushing “oh shit, I should have known!” moment upon the final reveal. Even then, powerful twists often foreshadow their reveal in the moments leading up to it, allowing the audience to potentially pre-empt the twist and feel clever, without giving them so much time that they lose the shock when the work itself confirms their suspicion.

But if we look beyond twists to moment-to-moment storytelling, the same principles hold true. Humans love pattern recognition, and in any story – especially any game – we engage in a host of cognitive processes that require us to build a working model of what we are being asked to understand and do. Just as the rules and surrounding framing of games encourage certain player behaviours, a story also generates its own implicit ‘rules’ in players’ minds.

Therefore, if you flag something loudly as being important – even unintentionally – players will expect a payoff. Failing to deliver in the right way diminishes trust. It can be like signing up for a debt without realising it; you’re still bound if you signed the contract. This isn’t to say that certain story directions are inherently wrong, but rather to urge consideration of the framing and lead-up. We must think in terms of the possibility space we’re creating for the future, and the obligations we are bound to by our narrative past.

Consequence VS Scope

Understanding acknowledgement versus consequence isn’t just essential for connecting with your audience; it's also incredibly helpful for managing your scope. To demonstrate how even moderate-sounding branching can go wrong, imagine deciding that every single dialogue option must send the story down its own permanent path.

An opening scene offers 4 choices.

Each of those paths then offers another 4 choices, leading to 16 paths.

Each of those spawns 4 more... an exponential tangle doubling outwards with every click.

Very quickly, a half‑hour text adventure that might feel like only 15 decision points to the player balloons into hundreds of millions of separate story nodes behind the scenes.

If you were to spend a modest half‑hour writing and testing each node, the total climbs to roughly 70,000 years of full‑time work.

If you then realise, deeply, that the player doesn't actually care about infinite choice, even if they sometimes think they do, and instead wants reactivity, salience, and consequence for the threads that typical narrative structures and your own sequencing have encouraged them to care about? Especially if these threads revolve around characters, who are often affected within the span of their own lives rather than branching every aspect of reality?

Then the solution becomes simpler. By constraining yourself thoughtfully, you're not limiting the player; you're focusing on the routes they are likely to care about, thereby delivering what they actually want.

Conversely, promising choice and then deciding to have nothingmatter, delivered in a way that feels pointless and betrays the game’s promises, is also problematic. This approach is hard to justify in a game featuring choices. Even for scope management, having a character’s individual dialogue or lines at later points be meaningfully impacted by earlier choices is not an impossibility that destroys an entire development cycle if handled carefully. In many cases, games offering choices with little emotional resonance, where nothing truly means anything, would have been perfectly valid, perhaps even stronger, as entirely linear stories.

What Save Game Imports teach us

Consider Dragon Age: The Veilguard's decision to limit imported decisions to just a very small handful from Inquisition while erasing hundreds from earlier games. While many did not like this, or had issues with the extent to which the remaining imports even mattered in a noticeable sense, the greater problem with Veilguard’s treatment of the series lies iin the kind of narrative importing it simply cannot prevent == the importing which goes on in the player’s own mind.

More than choice imports, seemingly ignoring and/or hand-waving previously vital lore and tonal elements felt dissonant for many in a lot of different ways – crucially, this dissonance only mattered because the studio had successfully built a world people actually cared about long-term, or else why would we care? Even beyond this, internally in the game itself, there are many ways in which the game seems uninvested in the stakes and reality of its own setting. There is a lot the game did really well — and sometimes, things that seemed forgotten at first glance were indeed raised later — but sequence and impression matters in these areas a great deal.

One might argue – as I imagine executives did – that a primary goal in creating narrative sequels for franchises is not to alienate new audiences or those who don’t remember prior instalments. However, the concept of “making things accessible and not too lore-heavy” is so frequently misunderstood that studios might as well actively avoid it for all the good it often does. Avoiding overcomplication for new audiences is simply good writing and narrative design in action, as no one wants giant lore dumps at any point because they’re only ‘lore dumps’ if they’re irrelevant by definition. The challenge? Obey the contract of relevance!

What we desire are characters behaving in ways that make them, and the world they inhabit, feel real. We need to feel this reality signified in tangible ways – ways that hint at a vast enormity beyond what we can immediately see and understand. We want this because the primary driver of the story should still be how these events emotionally affect the characters we care about, even as those events drive intrigue and plot. The paradox is that even well-written characters in their own right (Veilguard had some great party members) cannot exist in a vacuum if they feel like they’ve been transplanted into a setting rather than emerging within its texture.

When characters act in ways that ignore the world's established consistency, we get upset, whether as old OR new players, as the history of a world cannot be totally ignored by definition in a sequel. Players might wonder why no one mentions the Chantry at a crucial moment, or why a character whose entire belief system is shattered seems unfazed for hours afterwards beyond brief asides, to whatever extent the game encourages you (or encouraged you) to take these issues seriously. This illustrates how focusing acknowledgment on the wrong things, or ignoring elements previously established as crucial, can be counterproductive. It’s not that players always care about the intricacies of fantasy religion, but if your story is about fighting gods, ignoring such core elements creates the equivalent of MCU-ish disposability, reducing major threats to mere villains of the week.

However, even in the midst of this, one element helped overcome my issues with this storyline a great deal — one particular incident I wished we could have had much more of as an ingredient in the mix.

The moment the two major villains of Veilguard felt strongest to me was when they cared about each other – the arrival of one god on screen to rescue another with tenderness.

The moral complexity of showing antagonists as human is something many struggle with, but it’s a narrative necessity. Otherwise, why are their actions horror-inducing? Why else would we recognise these events as important for our minds and souls beyond the game itself? It’s why Solas, whenever he’s on screen, hits so hard – he cares and he lies; he is friend and foe, both and neither.

The Extended Cut for Mass Effect 3 was arguably less important for that game’s legacy than the release of the ‘Citadel’ DLC. Though set before the ending, many likely played it post-conclusion, allowing it to function as a de facto coda to the series. It succeeded because it added acknowledgment focused on what players often deem most salient in choice-based narratives: the fates of people and the emotional arcs based on established relationships and history. It addressed the player's specific journey with fictional people within the context of their own avatar’s history in that world.

Even if we don’t offer consequence for some things, we want the -lack of choice- to matter, or, we want -mattering- elsewhere, particularly in emotive interaction and the fate of imaginary people. It’s like the teacher says in the book The Courage to be Disliked — whether we want to hide away from other people is irrelevant, because you can’t live in this world and act and think and feel without it all, in some way, being defined by other people.

“Hell is other people” in the play No Exit, but so is heaven and, between it, above, below — anything that matters to anyone.

A few final examples

I’ll end with two very different examples illustrating this spectrum of choice versus consequence and emotional resonance – this time, regarding my own work and how I began my career — then, finally, a TTRPG game I played recently that really showed a lot of these concepts in action.

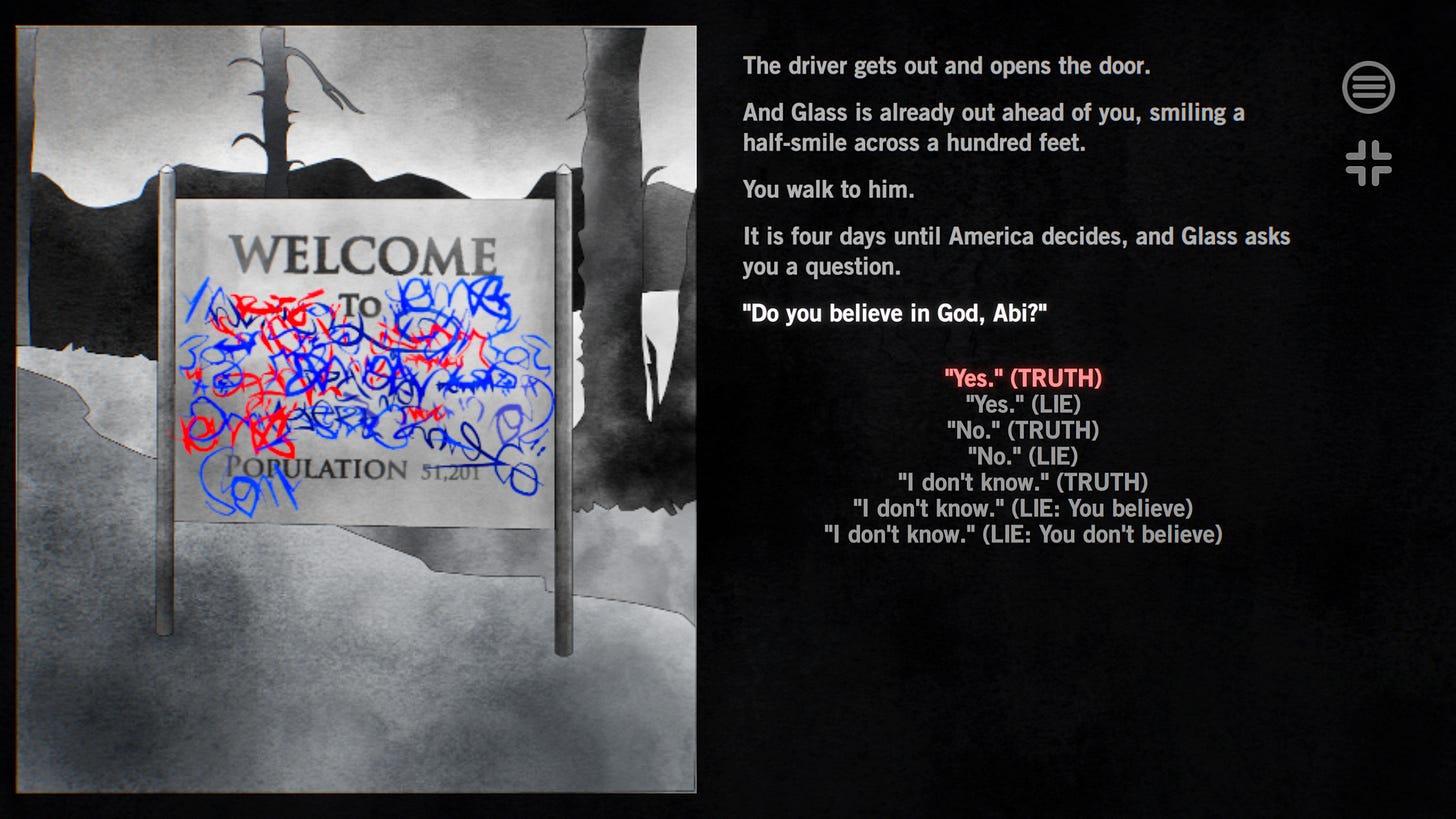

AMERICAN ELECTION

This is a text game built on choices where I explicitly tell the player from the start that their choices won’t ultimately matter on a grand scale. This is, of course, not entirely true. The choices do matter to the player in the moment, because how we conduct ourselves and respond within an emotional interpersonal context always matters, regardless of how little power we feel. Otherwise, why would workplace bullying or the relentless dehumanisation under capitalism affect us so deeply? Who among us can truly change the world with a single action, beyond the luck of a given moment?

NO MAN’S SKY (PATHFINDER Update)

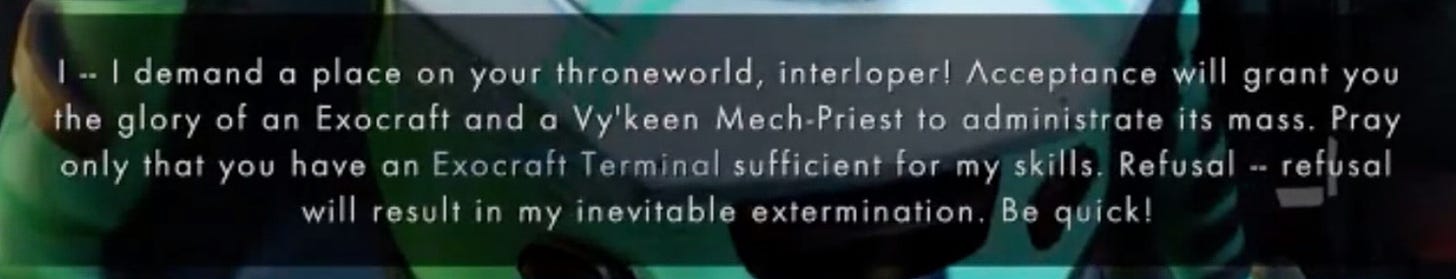

Consider the first update I contributed to, which led to me working on the much larger overhaul for ATLAS RISES. I previously discussed using rudeness as an early player hook, which aligns with many sentiments in this article. Here, I’ll discuss what that PATHFINDER update built towards: the very first moral choice in a game that previously lacked narrative branching of that kind.

I was asked to create a time-trial mission for an update centred around driving exocraft – get to location X on your base planet within time Y.

So, how do you approach that narratively?

It becomes almost like a mathematical equation if you think about storytelling, theme, why we like what we like, and the elements you’ve already set up. The plot itself generates what should come next.

Remember this framework if you’re ever stuck —>

What would people generally do/think/feel if faced with situation X in your story? Consider this from three perspectives, defining ‘people’ differently each time, transplanting them into your world:

1) People in *other stories* within your genre.

2) People in *real life* – those you know and those you can imagine ‘in general’.

3) You personally, the real you.So, faced with a character giving us a time trial mission, I needed urgency. Their 'caring' about the time limit could be a pure test of tech capability (a frequent, often lazy justification in game narrative), but this was near the end of a quest chain for an update preceding a content gap.

The quest-giver was someone we'd been dealing with after a rude introduction (see also this article) -

Thinking through story logic (Perspective 1: stories in any genre often build relationships or reveal motivations as part of their successful arcs), we wanted this interaction to have built towards something, fitting the flow while rewarding the player's engagement. If the rudeness and details worked to get you to view this visitor as anything more than a way of learning how to drive space cars, then how could we -do something- to reward that faith?

Next, I considered ‘real life’ (Perspective 2). What generally happens when people work together for a while? They get to know each other, forming some kind of bond through shared adversity. Why are people rude? Sometimes, others have been rude or harsh to them, or they're under stress. Horrible, irredeemable people exist, of course, but exploring that doesn't necessarily 'move things forward' in the way we'd want when triangulating real life with preferred story arcs. Making this solely about someone rudely demanding tasks would also raise plausibility questions about why the player character would continue helping them.

So, shaping this based on both story preference and real life? We love change and development in storylines, especially in people. Care ethics and character tenderness are particularly powerful, as seen in the Veilguard villain example. This also aligns with one real-life explanation for rudeness. If we want change in our story, revealing that rudeness stemmed from caring, building to a climax that reveals this caring, is incredibly powerful.

Therefore – this character was set up as having fled to the player's world from a pursuing force. Towards the end of the arc, he needs the player to intercept a crucial signal before it’s erased – a signal of great importance to him because…

He expects to hear from his loved ones, having fled those trying to kill him.

Getting there helps him and allows the player to learn more about dynamics likely found intriguing by this point – it connects to the initial rudeness that probably bothered the player and the mystery they've been lightly probing. It fits the genre's shape but avoids arbitrary or commonplace reasoning for a video game time trial tutorial.

When the player reaches the signal's origin – they discover the family is dead. The message was intercepted by those hunting their ally.

Upon returning at the mission's end, the ally asks for the message.

And here’s where we added something the game didn’t have before: a branching dialogue moral choice. A choice that did nothing, changed nothing mechanically, designed precisely around the existing system's limitations – not ignoring them, but inspired by them.

What would I care about in real life in this situation (Perspective 3)? What might I do? Fleeing everything I love is hard to imagine, but I could leverage empathy here. "Shit, should I even tell him? Will it just cause pain if he never expects to hear from them again anyway?"

So… a choice. A moment that doesn’t affect anything else in the entire game – but one that started my freelance career.

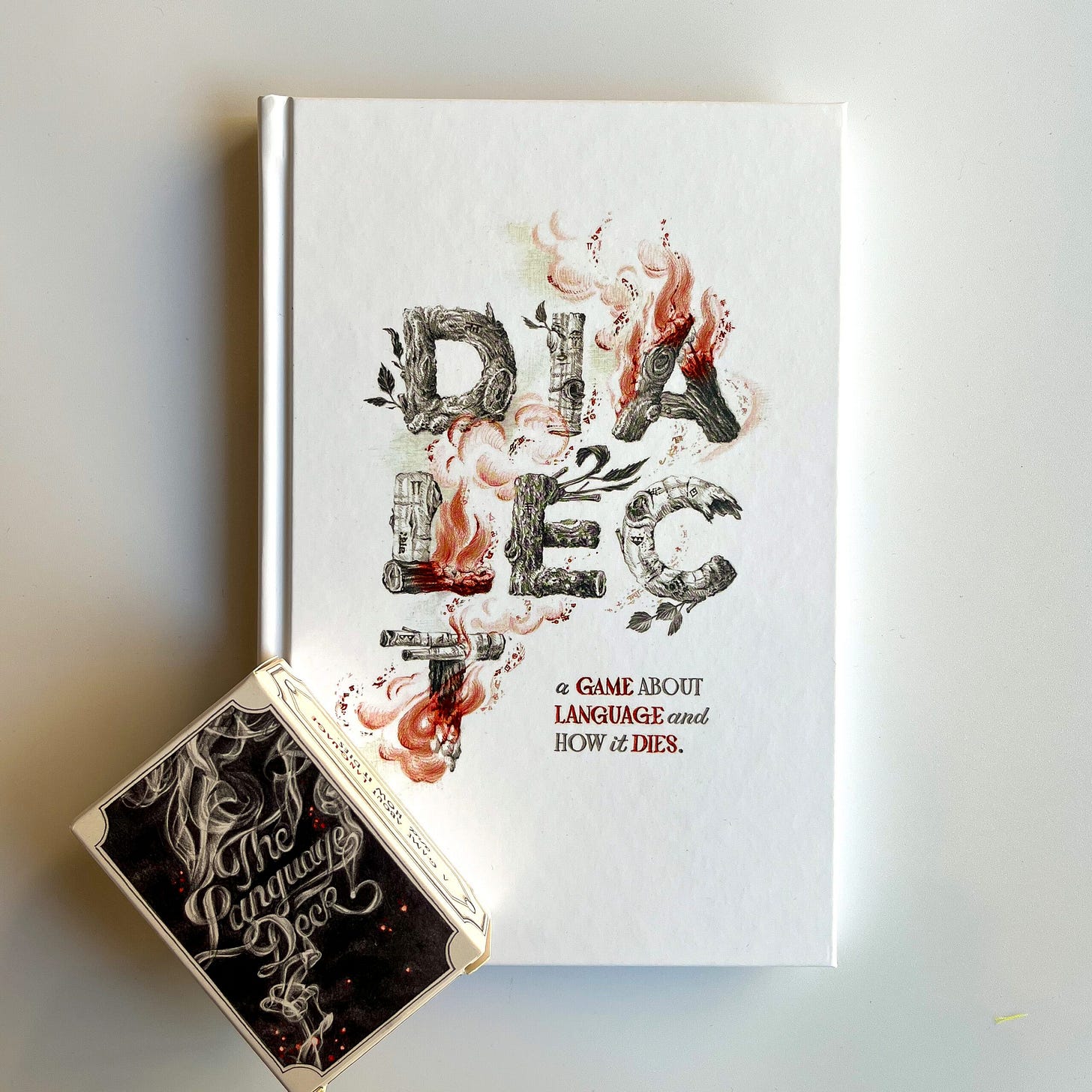

DIALECT (TTRPG)

A final example comes from the game Dialect. In this game, players collaboratively create words for their small group's dialect over time, switching between word-creation prompts and roleplaying the use of these words.

The game is fun but often leans towards tragedy, as it did in my recent experience. A word we used with a specific meaning early in our group’s existence had transformed by the time my character was an old man; mentioned by a youth, its original meaning was lost.

It felt genuinely sad to see the world ignore our intent, not because I perceived it as a 'storytelling mistake' or lack of attention, but because the fictional world found our wishes insignificant.

This resonates because the real world itself sometimes finds us insignificant, and the horror of this – the horror of time, power, and memory – hits precisely in that realisation.

What matters, then?

Ultimately, people often care more about the making of the choice than the specific result. They don’t even necessarily mind a choice being ignored or rendered moot, as long as the world and the situation justify and clearly frame that outcome as making sense within the narrative's logic. Narrative promises can be broken, provided the breaking serves a grander promise, and the betrayal itself contributes to that larger point and meaning. We just need to feel like a lack of mattering still matters.

See also these previous articles, which touch on some of these points in different directions —>