your game writing portfolio isn't working (yet): so, here is the stuff you -need-

Part 2: Thoughts on what to include, what to avoid, and how to present it

Note! The below is too long for email, email subscribers, so if you are not a premium subscriber and want to save a copy, you may want to visit the web version to save this locally.

(Some quick news also — I’ll be running my game writing workshop again (Writing Interactive Academy) starting May — https://gregbuchanangames.com/teaching . For a limited time, I am in a position to allow a number of discounts for those unable to afford the full fee, so if that’s ever been a barrier, now’s the time to go for it. The workshop and its community are not about jobs — no course can promise anything in that direction — but about skills and creation. We challenge ourselves to create interactive stories we could never have made before, whether beginners or professionals, whether we know any code or none. Of course this will be relevant for professional development and your career, but we dissolve that dichotomy — both are a means to make more cool stuff, or else what’s the point in doing this for a living? All you need is a willingness to learn and try. We have a few places remaining that I’m making decision about shortly — apply via the link above.)

Right — now for the main event you’re all here for —>

THE PDF OF WRITING SAMPLES

In Part One, we talked about the main goal of a portfolio -- not to provide a random assortment of information, but to present a cohesive story designed to win a reader over to you and your work. Understanding this underlying purpose (the “why” behind the task) is far more important than any specific set of tips, which is why I suggested viewing website and PDF portfolios as distinct documents with distinct purposes.

your game writing portfolio isn't working (yet): part one

You’ve probably seen countless tips about game writing portfolios—what to include, how to format them, whether you need multiple versions.

A website serves as your public "storefront display," designed for visibility and first impressions, showcasing highlights like screenshots or trailers. In contrast, a PDF portfolio is a curated collection of writing samples sent directly for specific job applications. Having previously covered website portfolios, we’ll now move onto PDFs.

A PDF portfolio offers hiring managers and studios an easily digestible, measurable-by-page-count single-document format for review—but it’s beneficial to you as well, even if that’s not immediately obvious. Essentially, a PDF portfolio functions as an alternate version of your CV or resume. Rather than simply listing skills and experience, it actively demonstrates those skills in action. This file shows a person taking a sprawl of information and reforging that chaos into a coherent, linear sequence, allowing you to selectively shape and refine your chosen samples to best suit a particular role.

In all of this, and all of the below — prioritize your mental health and creative passion. Allocate your time wisely and with self-compassion, rather than surrendering entirely to job searches. Often, investing time in creating new work is a better investment—boosting happiness, practicing the craft, and yielding potentially stronger samples for the future than excessive tailoring for uncertain outcomes.

Some writers hate the idea of marketing or publicising yourself, yet that’s exactly what a portfolio is. You may doubt your skills or willingness to self-promote, but you’re already doing precisely that whenever you write a great story. You sell your reader/player/audience on the experience—by hyping up suspense, emotion, and impact, letting them feel it, making them want to read more.

So?

Apply those storytelling skills here—it might just land you your next job.

Curating Your Samples

It’s important to set limits on how much we work on things like portfolios. Studios may lack clarity on requirements, processes can be chaotic or flawed, competition is often intense, and even strong, tailored samples might not always stand out or meet the quality bar against numerous other applicants. We should still devote time and care, but it's a matter of -extent- rather than giving the arrangement of this document your entire waking life.

Here’s a way of approaching this:

1. Start by creating portfolio PDFs customised specifically for certain jobs. Think about the types of games the studio is making or known for. Consider their imagined ‘type’ of writer, then align relevant samples from your work to help fit that while demonstrating your overall range of skills.

2. As you go, you’ll notice certain samples appearing more frequently than others. If some samples consistently show up, compile them into a ‘core’ document. If certain samples are specific to particular genres or tones (‘comedy’, ‘horror’, etc.), organise these into clearly labelled sub-documents for those groupings.

3. When preparing new applications, use the efforts of your previous thinking as a quick-start to save valuable time. This allows you to quickly prioritise highly relevant material based on previous decisions, reducing the effort required for future portfolios.

4. While prioritising relevance, remain conscious of overall length and balance. This doesn't mean other types of sample such as branching pieces cannot be included, but do consider overall page count and whether you have a more appropriate use of that space altogether. Some factors may override others—for example, if you have a particular project whose name and prestige is greater than your others, you may want to include some of that strategically to demonstrate not only skills but the fact you've worked on that tier of project. The same goes for things like work on high profile IPs.

So -- to emphasise -- while you can include impressive work even if it's slightly outside the studio's usual range, avoid a portfolio where all your samples feel tonally alien to their projects.

Imagine hiring someone to decorate your home, and their only examples are styles you find completely unlivable -- even if technically competent, would you trust such a designer with your own space? Especially if there are a great number of other designers available who -have- demonstrated the ability to do what you are looking for.

The same goes for all of these matters of 'should I push myself to write new material?' And developing skills. Even if we could reasonably infer you're great at writing, that isn't enough -- so are a lot of people.

Structuring Your Portfolio

Setting the Stage

If you show someone a writing sample, you are doing so because you think it demonstrates a skill in storytelling and narrative. But, by its nature as a snippet, it cannot possibly do that properly in the same way it would in an actual full creative work.

Therefore:

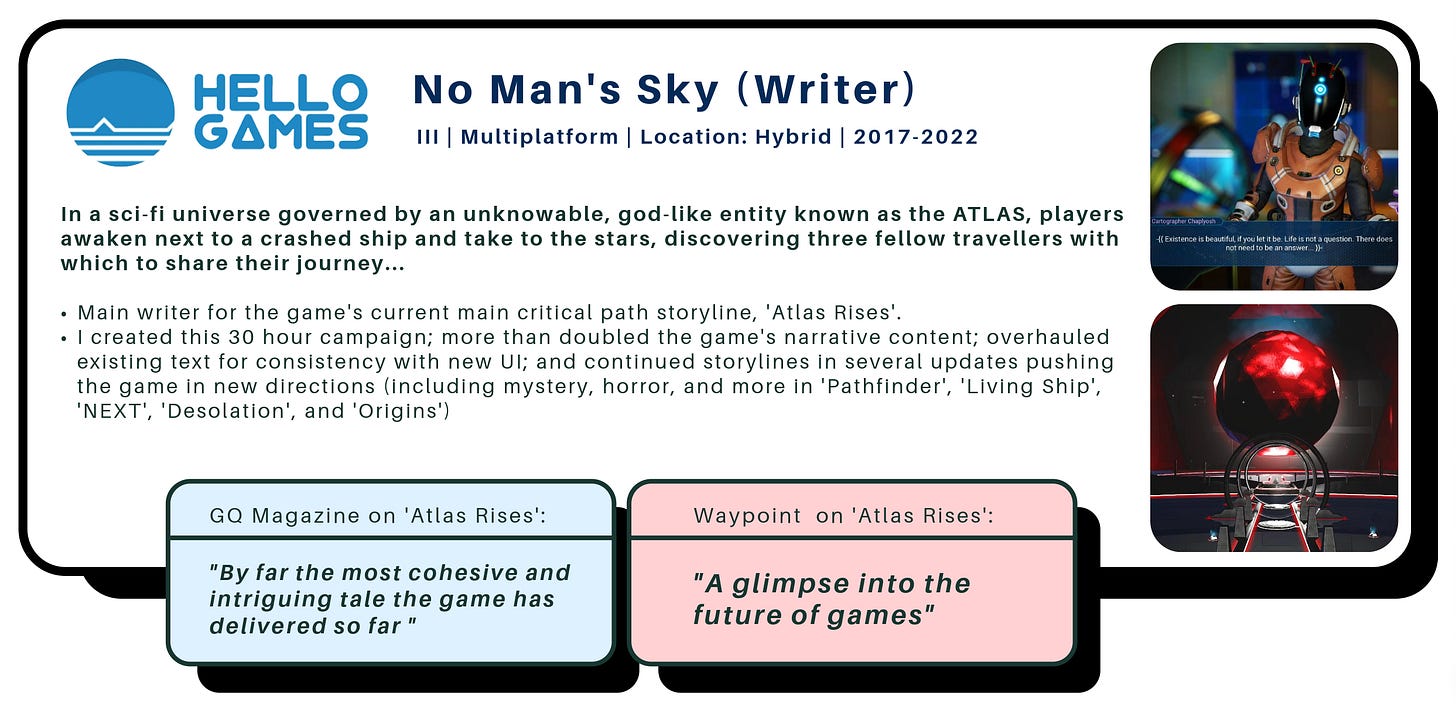

Make sure you introduce each sample properly, reminding people of what the project is, what kind of game, and your own involvement -- all in brief. For clarity and consistency, I personally use a modular header structure for each project—consistent both inside and outside my portfolio document:

When I say “structured,” I don’t mean it has to be bland. For my own, I have:

Header with Game Title + Your Role

Studio name or logo

Project type (AAA, AA, III, Indie, etc.)

Working Location

Dates you worked on it

Short Blurb or Logline (Summarizing the game’s premise succinctly)

Your Specific Contributions (What you wrote for this game; a condensed version of what might appear on your CV/resume, but here in brief)

Quotes & Images (I like to feature some screenshots paired with select player or critical quotes to highlight the kind of response others have had to the experience altogether)

Extra: It's very difficult to understand narrative if there is no setup, no explanation, no jumping off point. For this reason, below my header blocks I include italicised context to introduce *each* sample.

What To Include:

This isn't an exhaustive list, but rather a guide to the kinds of samples that effectively demonstrate a range of relevant writing skills for games.

Dialogue

Dialogue is a fundamental narrative skill that too many ignore when trying to get into game writing. You should be able to demonstrate:

accessible character-driven dialogue that also communicates gameplay objectives and goals.

interactions where the player can determine what one character is saying in a way that feels engaging and like a form of gameplay/strategy in itself.

linear non-interactive conversations where we don't resent the fact we aren't controlling things.

All of this means writing characters audiences care about and/or ‘like’. Demonstrating this quickly within the limited scope of a portfolio can be challenging, which is why aforementioned advice—like using context-headers to introduce each sample—is a really good idea for making your work feel less fragmented and random.

Avoid overly artsy writing. By this, I mean many writers will feature dialogue which might be better suited to an independent art-house film than the majority of paid video game gigs. This does NOT mean you shouldn’t try hard and have great writing in your portfolio. Just that there is great writing aimed at an indie niche, and great (accessible) writing aimed at a wider audience. Including a little of the former kind of writing in your portfolio is fine (especially if drizzled throughout, or featured primarily in lore or item description sections), but you need to make sure you can demonstrate your ability to write scenes where it's very clear what's happening if you want to get jobs on more commercially-oriented projects.

If you’re uncomfortable doing much of this sort of writing, you may need to ask yourself whether a career in writing games freelance for other companies is truly for you, or if you'd be better suited primarily developing your own games (with perhaps a limited amount of freelance work and consulting for projects which do fit your particular interests and design aesthetic). Remember, all these skills can be learned to various degrees, however, if you already have a decent level of writing ability in general - so don't despair if you're trying to write in this way and have not succeeded yet. The suggestion to reconsider your path is primarily aimed at those who feel they actively dislike the kind of writing described here.

And it’s important to reflect -why- this might feel like a problem for you as a writer, as it ideally shouldn’t. What is writing about other than human beings, and how do we know human beings, other than how we communicate? What is writing after all than a form of dialogue in itself? Often, an aversion to this discipline stems less from actual inability or distaste for dialogue at a deeper level, and more a lack of confidence or ability to fully frame the pursuit in your head. We need to challenge these things with a mindset that we can rise to the occasion and find ways to be better, not pretend that we would rather do other things.

Linear Dialogue (Scripts & Cutscenes)

Don’t fall into the trap of thinking studios only care about interactive dialogue. Many game writing roles involve substantial linear scripting, closely resembling traditional film or TV writing.

Some studios even require actual TV or film-style script samples during applications. However, to ask: “Can I just use my pre-existing screenwriting script and ignore all this game-specific advice?”... Which is a question I'm sadly asked quite frequently... the answr is no. Unless you’re extremely famous, you have a great number of competitors who either have both, or who have demonstrated games-specific expertise in a way that many studios have learned is utterly required to have a smooth experience. Leverage your TV/film background if you have it; studios will love it—but recognize it’s a -component-, not the entirety, of what you need to offer potential employers.

For linear writing samples (beyond those covered elsewhere, such as barks), consider including not just cutscenes, but multiple kinds of scene depending upon the kind of game you’re targeting. There are plenty of ways to show interaction with gameplay even within linear dialogue — think about the narration games such as Bastion feature, the way characters speak during interactive portions in Portal 2, or ambient party conversations in Baldur’s Gate 3.

Branching Dialogue & Narrative

I’ve included ‘branching’ within dialogue, but you can include types of writing that are not dialogue in moments like these, especially if drawn from interactive fiction projects like Twine or Ink games. The reason I say ‘dialogue’? With limited space in your portfolio, it's best to have samples that can demonstrate multiple things at the same time -- and few things are more enjoyable in text games than having dynamic conversations. And few things are more common in branching choice formats in commercial games than the dialogue tree -- therefore, it's a logical choice to have at least a decent amount of dialogue in whatever you select for branching narrative.

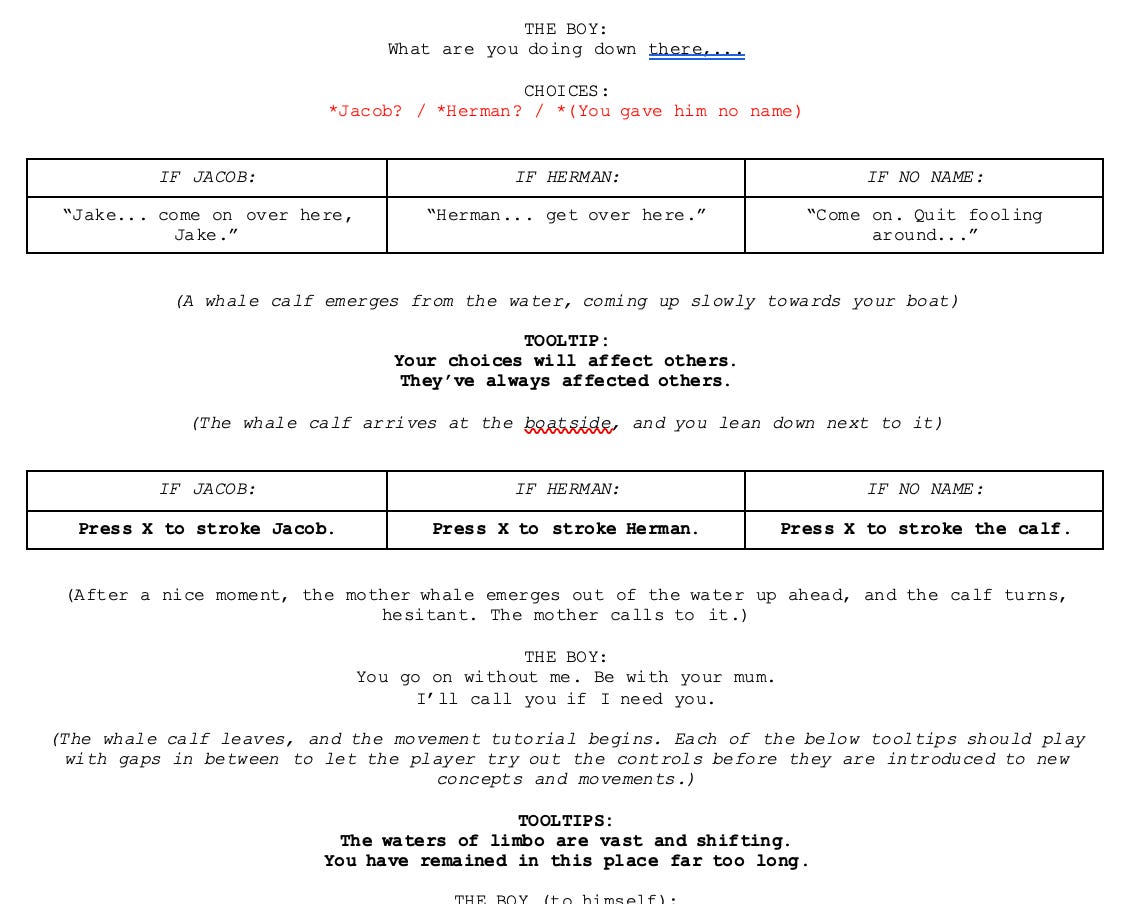

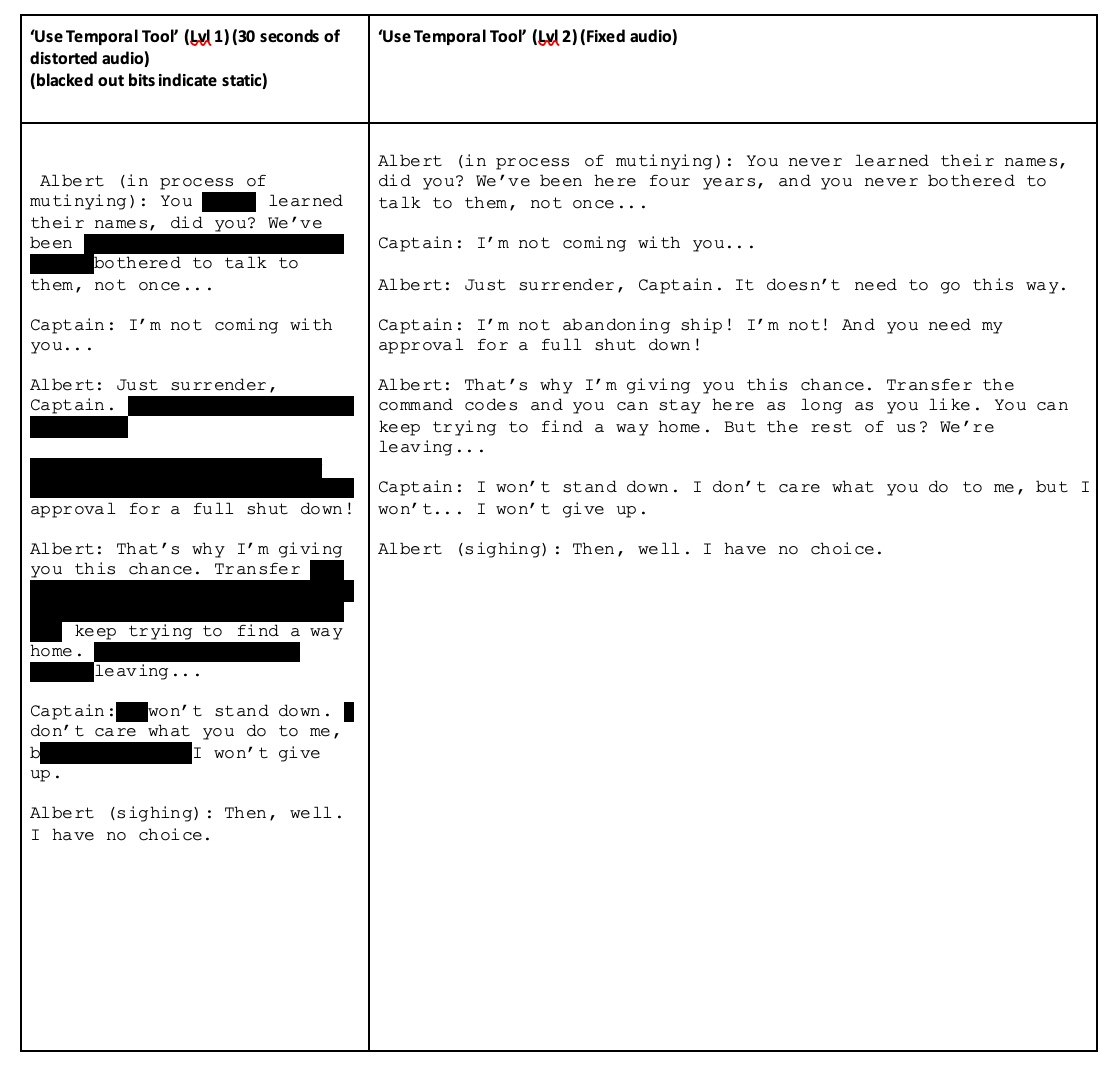

While providing links to playable versions of branching games can be a good idea, never assume reviewers will click them. Your PDF excerpt must be compelling enough on its own; the link is a bonus for those already intrigued. You need to therefore demonstrate your abilities in a way we can follow on the actual page. Consider using formats like tables and highlight your excerpts to show a few types of manageable reactivity --- for instance, simple emotional flavour choices leading to slight dialogue variations before reconverging; major choices that lead to two branches that might split just a little more before reconvening back into one column. If you include a major choice that does not loop back together, consider placing it late in the sample or ensure its full impact isn't detailed within the excerpt itself. When variables established through choices have important future impacts, you can always indicate these via ** asterisk footnotes and detail what will happen as a result.

Prioritize samples that efficiently showcase multiple relevant skills, such as dialogue quality, player choice, reactivity, and even gameplay integration (like tooltips), to best prove your versatility. Highlight your ability to write effective interactive dialogue that functions well as a united form of gameplay and narrative. Do not imply a desire to overcomplicate systems unnecessarily; bury your reader in an incomprehensible flowchart; or, indeed, feature giant segments -without- interactivity in these samples.

Why you want to avoid long non-interactive segments:

You want to avoid branching samples that lean heavily into long paragraphs of flowing prose writing unless specifically targeting narrative-rich titles such as Disco Elysium or Sunless Sea. And even for something like Disco Elysium, the long prose works so well because it's earned in the context of the actual experience—here, in isolation, it could easily create a false impression that you are an over-writer and unable to scope things down. What adds to the problem? Often long-overflowing-paragraph branching pieces have little dynamic back and forth interactivity and reactivity, resembling short stories in their appearance. You aren't demonstrating the kind of writing skills and types needed for most paid positions.

Now, interactive fiction is still totally legitimate to include if it avoids these traps - if it feels more like a dynamic experience or great flow of dialogue and action. If it feels more like a linear short story like the kind you'd find in a book, it may not be a great fit for this purpose when you're up against competition who have better selected samples to show these skills. (For this reason, also avoid short stories! Again, with the caveat of course that if you have an award winning short story or something, include a snippet perhaps and reference the award, but don't make it a focus.)

In my teaching, I stress the importance of pacing in text and of having some kind of extra interaction wherever possible -- avoiding nodes much longer than 120 words and avoiding single-choice-options in 99% of situations.

Why you want to avoid too much branching complexity:

Your game writing portfolio should be readable and easily followable - the more branches present in your sample and the more ways the story can progress, the harder-to-read it will be. This presents a tightrope balancing act for many of us in putting together our samples -- but the following insights might help in understanding the mindset of those who will see it. And remember, the -why- of all of this is far more important than any specific pieces of advice.

The truth is that the majority of branching dialogue conversations exist in games to allow players to define their character’s personality rather than drastically altering the storyline (although some such choices do). Demonstrating comfort with creating small, manageable branches that join up neatly to the same critical path is a useful skill. And, to reiterate, it is realistic -- the people screening your application and passing it to other departments may find it hard to get to grips with something that's hard to read on the page, quite understandably so, so don't make it difficult for them. This might also raise another problem in the mind of your potential employer: a sense that you might be naturally inclined to branch stories in a manner that might cost the studio a huge amount of time, resources, and money to achieve.

This doesn’t mean your interactive fiction projects -cannot- feature ambitious branching. Just, in the samples you choose to include in these PDFs and/or in the way you alter them anew for that PDF, try and keep the branching and visual complexity of the page to a manageable, easy to follow sequence.

Tables in MS Word and Google Docs are perfect for this -

(My sample above shows some branching in choices in a way that's visually clear, that doesn't alter the flow in an unreadable way, and which integrates spoken dialogue and cutscene reactivity without any segment being overly long. It also shows tutorialisation in the form of tooltips -- demonstrating an ability to tie into gameplay as part of the narrative. If a sample can show multiple skills rather than just one or two, it's often a great decision to include it over a sample that's only good at a single thing. Make it work for you.)

Dialogue Barks

Barks refer to one-line dialogue, often repeated outside the main storyline, that populate the game world to support gameplay features (e.g., "Grenade!", NPC one-liners, character select phrases). Despite their apparent simplicity, writing effective barks can be exceptionally difficult, often requiring dozens or even hundreds of variants to account for the many times players encounter them.

Your goal for a portfolio sample set is to show you're able to carry out game writing in a -functional- way. Effective barks should add an element of implied humanity and interest without being boring or attention-seeking (so avoid overly showy, metafictional, and/or 'weird' barks -- the whole point is to make lines that 'fit in'). You are not aiming to reinvent the wheel with this -- great barks exist to make the wheel so smooth in its operation that players forget there's even a wheel in the first place.

(As with anything, there are some exceptions to this last point, but for most of us, especially early career folks, your PDF portfolio is not the time or place for you to jump to that level of making exceptions. You just need to prove your worth in this regard first and foremost.)

Bonus: If you're able to show the same bark trigger manifesting in different line variants for different characters, you're outlining your ability to -vary character personality and voice- beyond just the specifics of the barks. Using a table or grid can make this a lot easier for people to tangibly see and notice as a skill.

Narrative Design: Structure and Flow

If you've designed some quests or narrative flows for larger missions in games, including a flowchart on a single A4 page would be a great idea if it's easy to follow and if it's sufficiently engaging in that format. The distinction between ‘game writer’ and ‘narrative designer’ is often blurred in practice, despite theoretical differences. Many studios use the terms interchangeably, so strictly defining yourself can limit opportunities both for the roles you apply for and the kinds of skill development you might seek out beyond this. Indeed, even if we try and consider ‘pure’ versions of both jobs, it's impossible, because regardless of their final deliverables, they inevitably draw on each other's methodologies; for example, writing branching dialogue is inherently narrative design because it directly shapes gameplay through choice.

This means that if you follow the rest of this advice, you’ll already have one sample with a greater level of design-led thinking. Beyond this, even for those who would define themselves more as ‘game writers’ first and foremost, there is one skill that's very hard to demonstrate in a constrained PDF sample -- the structural work and larger-scale writing that you might do for any piece of gameplay that's beyond 5 minutes in length. All this means that if we can find a solution that both allows us to demonstrate those macro-level story structure skills -and- which helps us show off narrative design, this is a great idea.

So, if there's room, consider including a short piece of abstracted narrative design in the form of a flowchart or diagram detailing a quest or mission flow in terms of narrative choices. This can be reverse engineered from fully-written games you might have worked on, taking a large segment and representing the conceptual structural movements of the story without showing the actual writing. However, as I said above, you want to avoid too much visual confusion and complexity in this document. Remember that your job is to entice the reader to -care- enough to read the flow is paramount. So, having header context like your other samples (a short intro to set the stage for this story sequence) is great, but I would also advise having some kind of outro to talk about the consequences of this mission/quest going forwards and how the player might be expected to feel about it. For the outro, we are emphasising why this all matters going forwards, which helps demonstrate a level of thinking about story and design that's difficult in short pieces.

Lore, Codices, and Found Texts

While much of my advice has focussed on dialogue and/or interactivity, it can be great to feature other forms of in-game text, particularly for applications for games that won't feature the other sorts of writing as heavily. When including these types of texts, it’s important to consider the frame of them: Are they from the perspective of a character within the game’s world? Are they documents that actually exist and could be found if that world were real? (This is known as ‘diegetic’ content.) Or are they forms of writing that only exist for us the players and audience outside the game (‘extra-diegetic’)?

Extra-diegetic material is often found in lore, codices, and in-game encyclopedias, though sometimes these can be framed (either in part or in full) as something created by people in the actual fictional setting.

For diegetic lore material, we have things like letters, ‘books’ (usually just a short extract), emails, logs, and more, presenting an authentic, in-world viewpoint.

(Note: I’m leaving out ‘item descriptions’ for now, which I've given a section to below as they're often a bit of a mix.)

Whatever you include, the samples should demonstrate your ability to build compelling worlds, convey information engagingly, and write compelling prose outside of direct conversation. Diegetic material can heavily assist things with its automatic partial inclusion of a character's mediating POV voice, but there are other advantages to non-diegetic examples in terms of their more natural potential to demonstrate concisely and effectively the ability to stick to the writing requirements of some projects.

Limit these examples to no more than a page of such content, unless the role is going to involve writing a bunch of this stuff. Select passages that are intriguing, evocative, or hint at a larger mystery or world detail. Avoid including lengthy, multi-page documents, especially in initial applications; reviewers often have limited time, and a shorter, impactful sample is more likely to be read and appreciated. You need just enough to showcase the skill.

Remember, you're giving reviewers a taste of your abilities. Overly long prose sections, even if well-written, can slow them down and dilute the impact of your portfolio as a whole. Bonus points if your lore entry subtly connects to or explains a gameplay mechanic, demonstrating an understanding of narrative integration.

Item Descriptions

Item descriptions are excellent for game writing portfolios because they highlight both gameplay functionality and narrative skill. Players consult item descriptions primarily to understand how an item functions and how it can be used, but a skilful description weaves in storytelling or flavour, all while never losing sight of its usability. Demonstrating the ability to balance these elements effectively suggests you are capable not only of crafting item descriptions but also handling broader aspects of game writing.

When choosing item description sets for your portfolio, select styles and tones that resonate with the project you're targeting. Mobile games often lean towards humour, while other genres may prefer darker (horror), mysterious (Dark Souls), or mixed narrative tones (Disco Elysium). Within each set, consistency in tone is advisable. Be cautious about incorporating real-world memes or topical references, as these might clash with a game's intended style or tone. If you anticipate a potential mismatch between your portfolio's content and the project you're applying for, reconsider including those pieces.

Because certain genres rely more heavily on item-based storytelling (particularly RPGs), I recommend showcasing 1--2 sets consisting of 4--15 item descriptions each, depending on the significance of item writing to your targeted project. Aim for a variety within your selected items -- weaponry and armour often have different requirements compared to essential story-driven items. Including a range of lengths can also demonstrate versatility, though generally, shorter descriptions tend to be more effective.

Although I recommended it in earlier sections for other parts of this portfolio, I would recommend avoiding excessive introductory context before your item descriptions. For most game item descriptions, they should already stand alone and already contain such context by their very nature. (Some quest-specific items may be an exception to this or there may be some extra context that's fun to highlight, in which case, still weigh up the value of including it vs saving space for other content).

CONCLUSION

As I said before — the underlying *why* of all of this is more important than the *what*. Your portfolio is designed to win over the reader -- so, as discussed, we want features arranged not as random information and data points, but as keys to a story presenting you and your work effectively. The PDF portfolio is that curated, targeted tool, sent specifically for certain jobs.

This means that you don't want to just blindly include everything from this guide for every application without thinking it through. It's more about curating your existing materials and, crucially, aiming to produce *new* materials in *new games* – often ones you can make yourself – to fill gaps and build that better, more cohesive story designed to win this future reader over. Remember the essentials: keep samples readable, avoid unnecessary complexity. But above all, balance demanding higher standards of yourself creatively with the trap of just ticking off boxes as fast as possible to fit perceived requirements. That latter path is essentially arbitrary.

A long time ago, I advised people made up samples where they didn't already have good ones for certain types of writing. So if you hadn't created a game with barks, make up some barks for a hypothetical game. Giving this advice initially around 2016 or 2017, though, it seems to have metastasized. Now people are missing the underlying reason and motivation behind that suggestion. The reason I suggested it was as a *temporary measure*, to be replaced as quickly as possible.

The thing standing in your way of replacing stopgap samples quickly is not the availability of jobs; it's your own creative output. Much of this type of writing *is* demonstrable through games that can be made with simple, free tools by yourself, without much coding knowledge at all. And even those types that aren't can often be created in combination with others at game jam events – particularly in-person jams where you get hands-on, time-limited experience with teams committed to being there, making them perhaps less likely to flake than many online versions.

If you can replace non-existent fragments from non-existent games with portions backed by, say, a screenshot or a brief playable build (the kind of thing you get from a jam), that's fantastic. And then, when you can replace those jam projects with paid examples? Great. You've moved from stopgaps to the real thing.

But even using stopgaps early on, I'd argue you're ill-served by *overwhelmingly* highlighting hypothetical content. Why? Because plenty of people applying for jobs *don't* need stopgaps. Employers can be more confident they can deliver. This doesn’t just have to be from paid games -- just, actual games.

The universe does not give us things just because we want them. While there's plenty that is unfair, arbitrary, confusing, or bad about many recruitment processes, many people submitting portfolios aren't really thinking through the perspective of how this document will be received or what the field looks like from the other side. This isn't a lottery. Yes, there's increased chance and variability now, to the point where even great, experienced writers aren't guaranteed a position. But that doesn't mean a slot machine is generating answers. There is still a person reading your work. And you are exponentially further away from your goal if you fail to realize that.

It's extremely appealing to believe you only need to write samples for made-up games to produce a portfolio of 15 pages or less. Because all that requires is writing 15 pages, avoiding the hard thinking and context those samples were *supposed* to have emerged from. None of them would exist in a vacuum in a real game, so you haven't actually demonstrated many of the core skills by presenting them hypothetically.

To systematically work on creating your own games should not be an upsetting prospect. Because if it is, why do you want to do this professionally?

your game writing portfolio isn't working (yet): part one

You’ve probably seen countless tips about game writing portfolios—what to include, how to format them, whether you need multiple versions.